Remembering Denis Goldberg, and the life he lived to the full.

By Marion Edmunds

Director of Sentenced with Mandela, the Denis Goldberg Story, 2011

May 2020

I first met Denis Goldberg when I was a parliamentary reporter. It was a Friday afternoon and the corridors of power were quiet. An emissary from the Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation rounded up the few journalists still at work, to attend an impromptu press conference about water-borne disease. The then minister, former uMkhonto we Sizwe operative, Ronnie Kasrils, introduced his special adviser, Denis Goldberg, as an “old comrade” with many insights, a trained engineer who was best to talk on the issue. Denis’ chief message was that South Africans should be encouraged to wash their hands, regularly, in order to combat disease. At the time, I callously shrugged my shoulders, guessing the item wouldn’t make the evening news bulletin and wondering what more the special advisor might have to say. With hindsight, in this time of Coronavirus, his words have a prophetic wisdom.

I found that out much later when embarking on a documentary, Sentenced with Mandela, The Denis Goldberg Story, that Ronnie Kasril’s special adviser had a great deal more to say. He generously agreed to be the subject of a biographical film, on the condition that I film in parallel with a German documentary-maker, to whom he had already made a commitment. Denis was scrupulous in that way, and did not abandon a promise, although it complicated the filming for him. To be the subject of two camera crews simultaneously, in your seventies, is a feat of endurance.

But then Denis had endured so much already by the time I got to know him properly, not least a prison sentence extending beyond two decades. That price he paid for his idealism and political action in his prime cost him the best years of family life and brought him huge pain. And he tolerated the suffering with an unbowed sense of optimism, with good humour, and great practicality.

His life is a series of distinct chapters, playing out in contrasting locations. It starts with Denis as a tousle-haired, cheeky looking boy in the Cape Town working-class suburb of Observatory, son of Jewish immigrants who schooled him ideologically in communism. He remembered his parents feeding workers on the picket-line and demonstrating deep sympathy to the poor and downtrodden of all races. He also remembered being chased with a knife by a butcher with Nazi-sympathies, who would shout at him as he walked to school: I am going to get you Jew-Boy! Denis kindly took me and the camera crew back to Observatory to drive past the landmarks of his childhood, trawling his private spaces for memories.

Then as a young adult, he became involved in the Modern Youth Society, young people defying the racist conventions and laws of the South Africa of that time, to meet across the colour-bar and talk about politics and how to build a better, equal, non-racist world. I located jerky old footage of these young people, playing games, singing songs and marching together in a display of socialist solidarity and idealism. During this time, he met Esme Bodenstein, whom he married, and who paid a huge price as the exiled wife of a jailed communist revolutionary, a single mother to two children, living across the sea from the apartheid prison which held Denis for 22 years. An old film which I was lucky to be able to use in our documentary reflected her disillusionment with the life she ended up living in London when she had to fall very much on her resources and make the best of it, including taking in lodgers to supplement the household income.

For Denis had become deeply involved in the revolution and he gave it his all. He joined the South African Communist Party, he organised protests against the apartheid government, and he signed up to the ANC’s armed wing, umKhonto we Sizwe. He helped to organize its first training camp in the rural area of Mamre in the Western Cape. Yes, we went there too with him, and walked around the empty field where they had drilled the new recruits to the revolution. As he conjured up memories, with veterans whom he had brought with him for the film shoot, he invoked the laughter of youth, and the jokes that had been shared, as much as the seriousness of the task at hand. He taught the cadres how to make bombs and sabotage cars and print pamphlets among other things. He spoke a great deal about a gifted young township leader called Looksmart Solwandle Ngudle, who was arrested, shortly after the Rivonia arrests. (Looksmart was one of the first South African political prisoners to die under interrogation by apartheid police and was found dead in his cell in Pretoria, the tragic news conveyed to Denis in his. I would not have known about Looksmart, if it had not been for Denis, so eager to share the story of his life with other participants in the Liberation Struggle.)

As a university-trained engineer, Denis was a font of wisdom about explosives and possible targets – electric pylons, railway lines and underground cables for example. He went to Johannesburg on a top secret mission for MK and had the misfortune of being at Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, just outside Johannesburg, when the police swooped down on the hideaway to arrest the ANC’s National High Command, with accompanying incriminating evidence. Denis’ mission had been to research what was needed in the way of explosives and hardware to start a revolution and he arrived at Lilliesleaf, fatefully, with his notebook.

“I was to investigate the manufacture of weapons and the explosives we’d need: hand-grenades, landmines, detonators, remote detonators and so on,” he told me in the laconic, quiet voice of an accomplished raconteur. “You have to make some notes. And unfortunately I was captured with the notes in my pocket.”

So Denis found himself with Nelson Mandela and seven other accused, one of only two white men, before an unflinching apartheid-era judge, Mr Quartus de Wet, facing a possible death sentence for sabotage. This became a politically defining trial for apartheid South Africa. Sharing the dock were the ANC’s heavyweights: Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Rusty Bernstein, Raymond Mhlaba, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni. Denis was on the wrong side of the law, but he was in good political company. According to Joel Joffe, the lead defence attorney, Denis was persistently upbeat despite the difficulty of the situation and the cruelty of the police, who did not spare him their anti-semitism and rough interrogation techniques. His ebullience reached the point where the legal team feared he might jeopardise his position under cross-examination. He made rude signs to the policemen with his middle finger, and seemed always to be enjoying himself, cracking jokes, smiling and chatting. But when his day on the stand came, the defence team were relieved. Denis performed well under pressure. And one of his great utterances came at the end of the trial, when Judge de Wet handed down a sentence of life imprisonment rather than death by hanging. They had escaped the noose, and Denis shouted out when his mother called for the judgement: “Life! It’s life for living!” It was a moment of supreme defiance, as he was then taken away to spend the next two decades and more behind the cold, grey walls of Pretoria Central Prison. It was June 1964 and Denis was only 31 years old.

Denis in the dock of Pretoria’s Palace of Justice, remembering the Rivonia Trial in which he had faced the death sentence. He was sentenced to life imprisonment along with Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders.

So, another chapter started. Denis was separated from his co-accused who were dispatched to Robben Island and as a convicted white revolutionary, restricted to the political wing of this Pretoria Central Prison. There he became something of a leader to a small dislocated community of white prisoners who came and went over the years. Denis retained his sense of conscience and his great compassion. He had planned to escape from the prison with three others who hatched an elaborate plot, but at the last moment, turned down that chance on the grounds that he was too old and may jeopardise their flight. They slipped out of the prison by making wooden keys, and he stayed on, becoming one of the seniors. He nursed with care and compassion the ailing Bram Fischer, who had represented him and others at the Rivonia Trial. Sapped by cancer, the once powerful defence lawyer declined painfully in prison and Denis carried him practically and emotionally to the end. Denis lifted spirits with his jokes and home-spun wisdom. He organized and advised. He campaigned for political prisoners to get newspapers. He painted the lines of the baseball court within the prison, where the prisoners played for recreation. “I painted those,” he chortled to the camera proudly when we went back to this place of containment, many years back, a smile on his face, despite the closing in of memories.

Denis reflecting on his long prison sentence on a visit back to Pretoria Central Prison with a camera crew

Of all the moments I was privileged to share with Denis, his visit back to Pretoria Central Prison was one of the most moving. While touring the prison, he turned to one of the warders, and said spontaneously:

“Look after the people here, I know they’re difficult, I know prisoners are not easy, but it’s so awful for them.” Denis had been shaken by the warder’s confession that she might not be able to survive imprisonment herself.

“We have to treat people like people,” he continued. “Before it was only punishment, I didn’t spend twenty-two years here in prison to have the same kind of prison for people in the future. If you couldn’t survive one day, you’re doing something wrong.”

The other extraordinary moment was on Robben Island. For the sake of the German documentary-maker and myself, Denis organized a trip to Robben Island with fellow Rivonia Trial accused Ahmed Kathrada. Denis had carried with him a sensitivity about his release in 1985 after 22 years in jail in Pretoria. It had been offered by the apartheid government on the condition he denounced the armed struggle against apartheid, and the offer was engineered in peculiar circumstances. Denis eventually signed the document as a passport out, possibly realizing that his resilience in jail was waning. But on quitting South Africa, he denounced his undertaking at a press conference with the ANC in exile in Lusaka. But some within the ANC and the SACP never forgave him: integrating into exile society in London was emotionally and politically difficult for him. He didn’t expand on this part of his life in the interviews we did, but many of his friends alluded to the irony that his release from Pretoria Central had been a very challenging part of the prison experience.

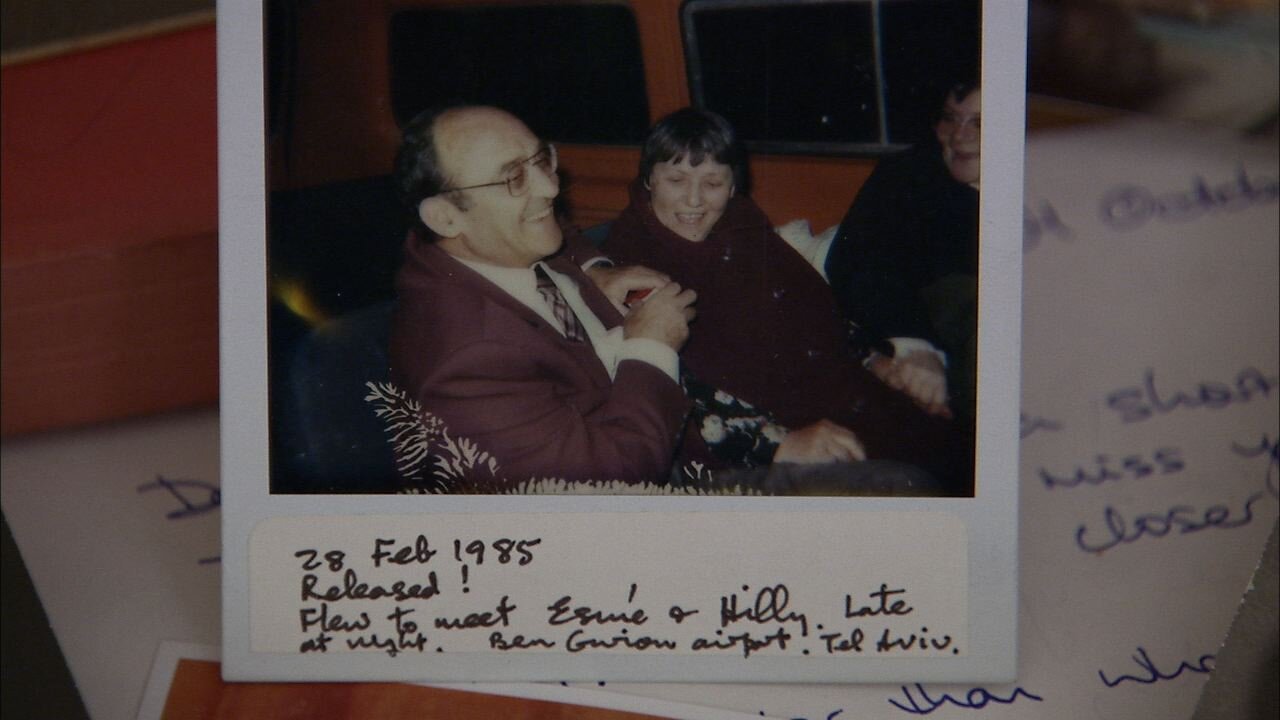

A photo of Denis re-united with his family after 22 years in jail, filmed with his private letters in the documentary, Sentenced with Mandela, 2011

On Robben Island, in Nelson Mandela’s cell, Ahmed Kathrada gently told Denis that he and the other Rivonia trialists on the Island had completely understood why, in 1985, he had to quit prison when he did, and that they had held no grudge, only sympathy.

“You know people feel that Robben Island was the worst, it was not,” said Kathy turning to Denis. “We were together, the white comrades were just a handful. We were thirty of us here and then we had hundreds and hundreds in the cells there, so again one of things you wanted in prison is companionship, the more the better. Denis and them didn’t have that.”

A great heaviness seemed to leave Denis at that point, and although we stopped recording the interview, as time in Mandela’s cell is always limited, it felt as if it were the right moment with which to end the documentary. In a sense, it was the end of documenting that very long chapter.

But Denis had more chapters since prison, some spent in London, some in Germany and many in Cape Town, where he was based in his simple but beautiful Hout Bay home, adorned with interesting art. He never lost his faith in life, in the creative arts, in relationships, in the power of people to bring about change and in the ANC, the organization in which he invested so much, which had given him a creed to live by, and in whose service he had personally paid such a high price for a new society. He involved himself in uplifting the community around him, channeled money to good causes through his foundation. To encourage others to do the same, he was always available to speak and gave interviews, explaining his perspectives through simple parables drawn from his own life. He stood up against ANC abuses with other veterans, he gave advice and direction to the youth.

Once the documentary was completed, I felt sufficiently comfortable to visit him with my small children, but after that we lost touch. However, a tango-dancing friend of mine reported a sighting relatively recently at her tango club. Denis was there in his wheelchair to accompany his partner who loved to step out. What a fitting way to end such a turbulent, purposeful and varied life, living life fully and sensually to the very last dance.

© Marion Edmunds May 2020

Sentenced with Mandela is the story of anti-apartheid activist Denis Goldberg, the only white revolutionary to be convicted at the Rivonia Trial.