Yesterday evening I found my father in a cheerful frame of mind when I went up to his flat to prepare him for bed. We had had a good weekend – autumn sunshine had bathed the landscape with golden light; red, brown and yellow leaves were floating down in a gentle, hot wind. As evening fell, and I walked up the brick stairs, a large full moon rose into the darkening sky in front of me. My mother-in-law had come to stay, and my father had recognized her from previous visits.

It was good to have Oma come to visit, I said as I helped him with his pyjamas. I find myself planting these questions in our conversation, partly to fill in the empty sound spaces as we go about our mutual chores, partly to jog him into talking, as he says very little during any given day, just a handful of phrases between dawn and dusk. But also, if I am honest with myself, I ask him questions to test his ability to respond, measuring the logic of his answers and the strength of his recall. Did he remember that his counterpart from the other side of the family had been here, they had greeted each other and had eaten cake on the stoep in the hazy autumn-coloured sunshine a few hours ago? Or has he already lost the imprint of that experience?

He repeated her name with a quizzical look. And then memory must have returned, and it broke over his face like a light.

“Yes, that was nice,” he said, with a clear understanding of what we were sharing.

“She’s turning 80 this year,” I said by way of furthering the conversation. He drew up his mouth in a sympathetic grimace. And then looking at me sideways as he pulled on a pyjama leg, and with just a little twinkle in an otherwise deadpan face, said:

“I’ve done that.”

We had a giggle together. At 87, he can still employ wit. I felt relief; he is in some way with us in mind and spirit, as well as body.

Yet, so often his Dementia plunges him into a deep fog, where memories seem to loom shapeless when called for, with only a suggestion of what they might have once been or what they might now mean. Or the memories and intentions are there, but his ability to articulate and describe them has atrophied and he starts a sentence only to sputter to a silence before the big reveal, leaving us both in anticipation, and he, holding up his hands in frustration. This inconsistency is challenging – how to calibrate his care to include the on-moments and the off-moments, unpredictable as they are. And then how to work out the rate of his deterioration. So for years now, every time I bring him tea in the morning, serve him a meal, change his clothes, bid him good night, I am looking for clear signs that his synapses are still pinging, so I can place his behaviour on the spectrum, and measure his abilities, to prepare for the next step.

The Dementia Detective and in-house sniffer dog aka River

I have become a Dementia detective, using our everyday interactions to put puzzle pieces into a shifting landscape. But it is a picture that forms and reforms all the time, like an infinite video time-lapse, itself elusive, never settling into a final landscape.

The more I burrow into the detective metaphor, the more truth I find in it. The other great sleuthing challenge is trying to predict what he wants to say, or what he fears, from the few words he has said, which seldom add up to a whole sentence or thought. I have to draw on all our shared references and memories to attempt to frame his words in a context, and then run with a hunch. I stand in for the tired, collapsed part of his brain, whether he is reliving an experience from his youth or something that happened this week. I intuitively use his personal history to help him out of his mental logjams – this reference possibly to my mother, that trip abroad, this job at the university, that cousin or a brother.

This week he was constantly referring to “a fellow” who was coming to visit, and I could not work out who this might be. He was anxious about “this fellow” and walked up and down, checking the gate. I circled around a number of scenarios, attempting to pin an identity on the invisible person. Then we realized that he was referring to the new afternoon carer, with whom he had not bonded and about whose visit he was becoming more and more anxious. Once the penny dropped, much of his unexplained recent behaviour fell into place, and we decided to discontinue that carer, and seek out somebody else. But this revelation came after much puzzling, and few clues.

Looking for tracks in the sand…constantly on the trail of some thought process that does not fully reveal its origins or its destination

And now with all this first-hand experience, I find myself becoming a Dementia Detective in other ways too – in finding out more about the prevalence and nature of the disease which is referenced so widely, but of which I initially understood so little.

A social worker referred me to a seven-week online course provided by experts ten thousand kilometres away from here. It’s called Understanding Dementia, and it is presented by the Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre at the University of Tasmania, an island off Australia. It’s a free online distance learning course called a MOOC, an acronym which stands for a Massive Open Online Course. That means that anybody can sign up from anywhere in the world to learn and interact digitally, and there is no criteria for entry, beyond connectivity. Since 2013, the Understanding Dementia course has received 330 000 enrolments from all around the world.

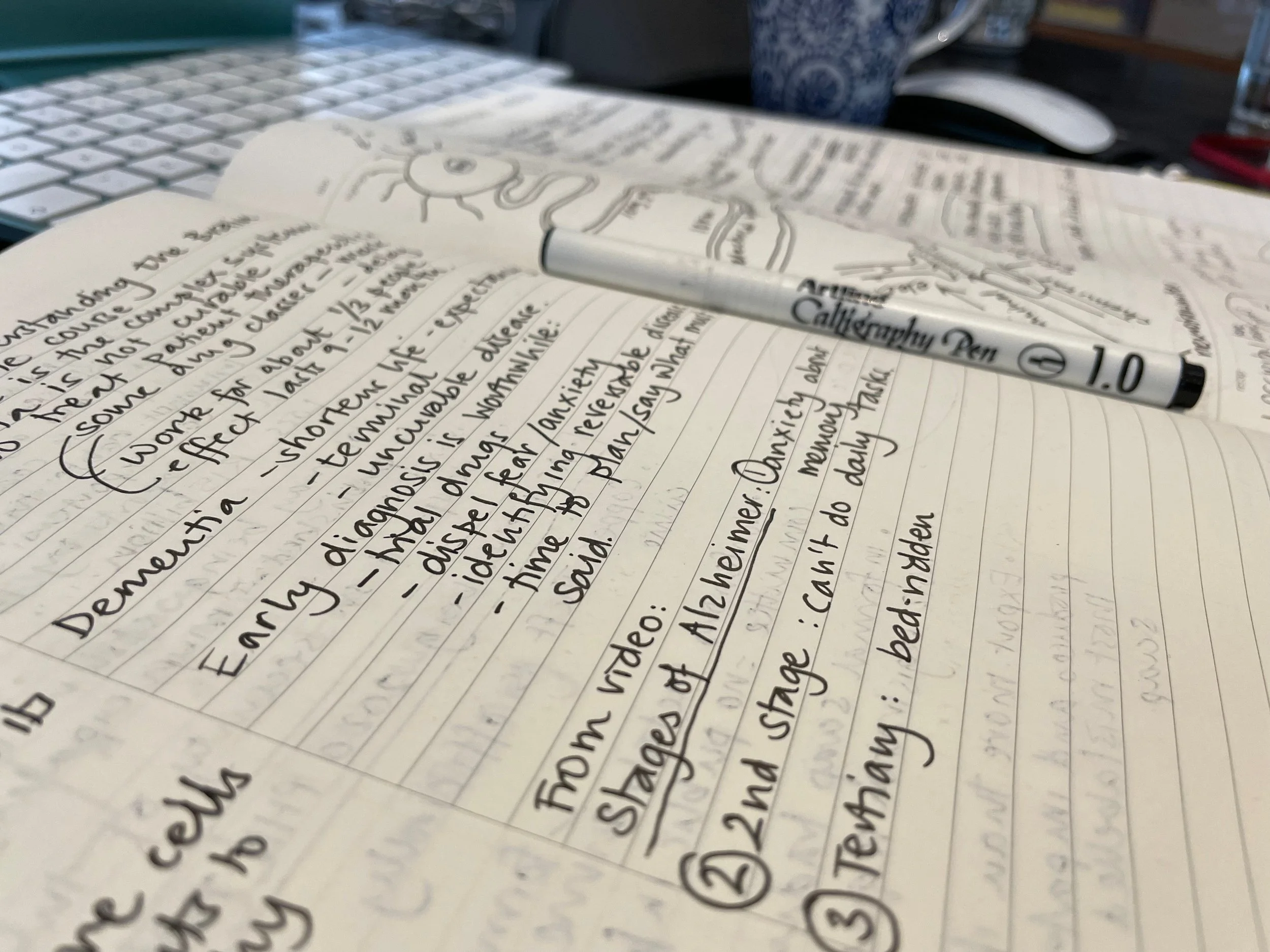

Study notes on Dementia for the seven-week MOOC - see link to do the course

I now am one of those. The course has given me understanding far beyond the medical consultations we have had about my Dad’s health. The MOOC walks a student through Dementia – a scientific explanation of what happens on a cellular level in the brain of a person suffering from dementia, the nature of the diseases that cause dementia, and perspectives of how care for afflicted people is evolving, including the need for palliative care. The next course will be held in July this year – here is a link to anybody who feels they might need the information provided: https://mooc.utas.edu.au/landing/udwp.

I would recommend it. Beyond the information, I found it soothing because it linked me to a giant global classroom of people who are on the same quest for information and comprehension. The teachers were educated and compassionate, showing a remarkable degree of academic humility.

A brief google has shown me that this is not the only online course available. In order to encourage enrolment, many of these courses quote the dramatic and stark statistics of how many millions of people suffer from dementia globally. Many remind us that dementia is currently the seventh leading cause of death among all diseases, and there is currently no cure.

These figures, though useful, relegate me and my father to a single digit in a vast, growing statistic. Fresh out of COVID, I find them overwhelming, as I do find much of the information on the web about dementia. So it is not surprising that while googling all this bad news, I found myself snooping in a different space, and signing up to a free online course provided by Yale University on the Science of Happiness. If cognitive time is short and unpredictable, then carpe diem!